Inside a home on 60th Avenue in East Oakland, you’ll find longtime Oakland resident Rebecca Washington-Ogbebor wearing what she considers a casual outfit: a long flowy dress with traditional African patterns in red, navy, and green, complete with a matching headwrap.

A seamstress and clothing designer, Washington-Ogbebor sewed the dress and headwrap herself.

“When I started making clothing, I would always get this spiritualness around me,” she said. “It let me know that I didn’t have to conform and do things the way the world wanted me to do it—I could do it my way.”

Wilsdom African Designs, 2557 60th Ave. Open Monday from 12-6:30 p.m., Tuesday through Friday from 11 a.m.-6:30 p.m., and Saturday from 12-5:30 p.m. By appointment only. Closed Sunday.

Washington-Ogbebor is the founder and owner of Wilsdom African Designs, a traditional African clothing boutique she runs out of her home near the Bancroft business district. With fabrics sourced from Ghana, Senegal, Mali, Nigeria, and other African countries, she hand-crafts clothing for just about any occasion—bridal gowns, graduation caps and stoles, dashikis, sarongs, and kufi caps, to name a few. She said it takes her anywhere from one day to a week to complete a dress.

Beyond clothing, Washington-Ogbebor’s shop also sells earrings, Kwanzaa gifts, and beauty products such as raw shea butter, African black soap, and body oil.

The impetus for launching Wilsdom African Designs came to her in 1990 when she would host “Tupperware parties,” social gatherings wherein Tupperware consultants would showcase and sell the company’s latest products. At those parties, Washington-Ogbebor’s friends often asked her where she got her clothes, which she sewed herself with textiles from Nigeria.

Seeing their curiosity as a new business opportunity, Washington-Ogbebor began hosting fashion shows to unveil her designs. She created dresses, skirts, and headwraps and had two of her friends model the clothes at other people’s houses.

“That’s how Wilsdom took effect—me doing Tupperware parties, but [with] African clothing instead,” she said.

Word spread of her work. She started selling clothing out of a warehouse flea market on 23rd Avenue and East 14th Street, eventually moving her business to Foothill Square in deep East Oakland.

In 2002, Washington-Ogbebor relocated her business to work from home so she could help take care of her 15 grandchildren. Many of her grandchildren have modeled her clothing on the store’s website and helped her create Yelp, Etsy, and Facebook pages.

“It’s not that I want to be Rachel Zoe or Michael Kors or any famous designer out there. I’ve just wanted to take care of my family,” she said.

Over the years, she’s built up a loyal clientele across the country. Her first big order, she recalled, was for mudcloths for a Native American tribe in Utah for $1,200. She’s made graduation stoles for many schools, including 100% College Prep in San Francisco, College Track Oakland, Hayward High School, and Pasadena City College. She’s also sewn bereavement attire for babies and adults who have died and face masks with traditional African patterns for hospitals and health care professionals during the COVID-19 shutdowns.

In addition to using social media to promote her small business, most of Washington-Ogbebor’s customers have heard of her through word of mouth.

“I like to say I’m hidden, but not hiding,” she said.

A woman of faith, Washington-Ogbebor said the name of her business came to her in a “revelation from God.”

From the Louisiana bayous to the Oakland flats

Born in Natchitoches, Louisiana, Washington-Ogbebor was raised by her mother; grandfather, a member of the Choctaw Nation; and grandmother, whom she described as a “Southern belle.”

While in elementary school, she moved with her family across the country to the Brookfield Village neighborhood of Oakland. The eldest of five children, she attended Brookfield Elementary School, Madison Park Academy, Castlemont High School, and Skyline High School.

“We were able to roam freely and play throughout the whole block until the streetlights came on,” said Washington-Ogbebor, referring to her brother and three sisters.

At age 12, she learned how to sew by observing her aunt. “My aunt was a full-figured woman, so she would make things for herself and I would be right there with her,” said Washington-Ogbebor. “When I started sewing, it was just natural. I can’t explain it.”

Washington-Ogbebor is no stranger to hardships. Growing up in the South, she was bullied for having different hair from other girls at school. “I grew up looking for my people … with this skin and hair, and I wasn’t seeing people that looked like me,” she said.

In January 2000, one of her children, Andre D. Stanley, was fatally stabbed at age 24, leaving behind five children. He was the first homicide victim that year, according to the Oakland Tribune.

During the pandemic shutdowns, Washington-Ogbebor’s father and stepmother, both of whom she was close to, died of COVID-19 eight days apart.

“It’s just been a journey,” she said, describing the deaths of her loved ones as “the heavens opening up.”

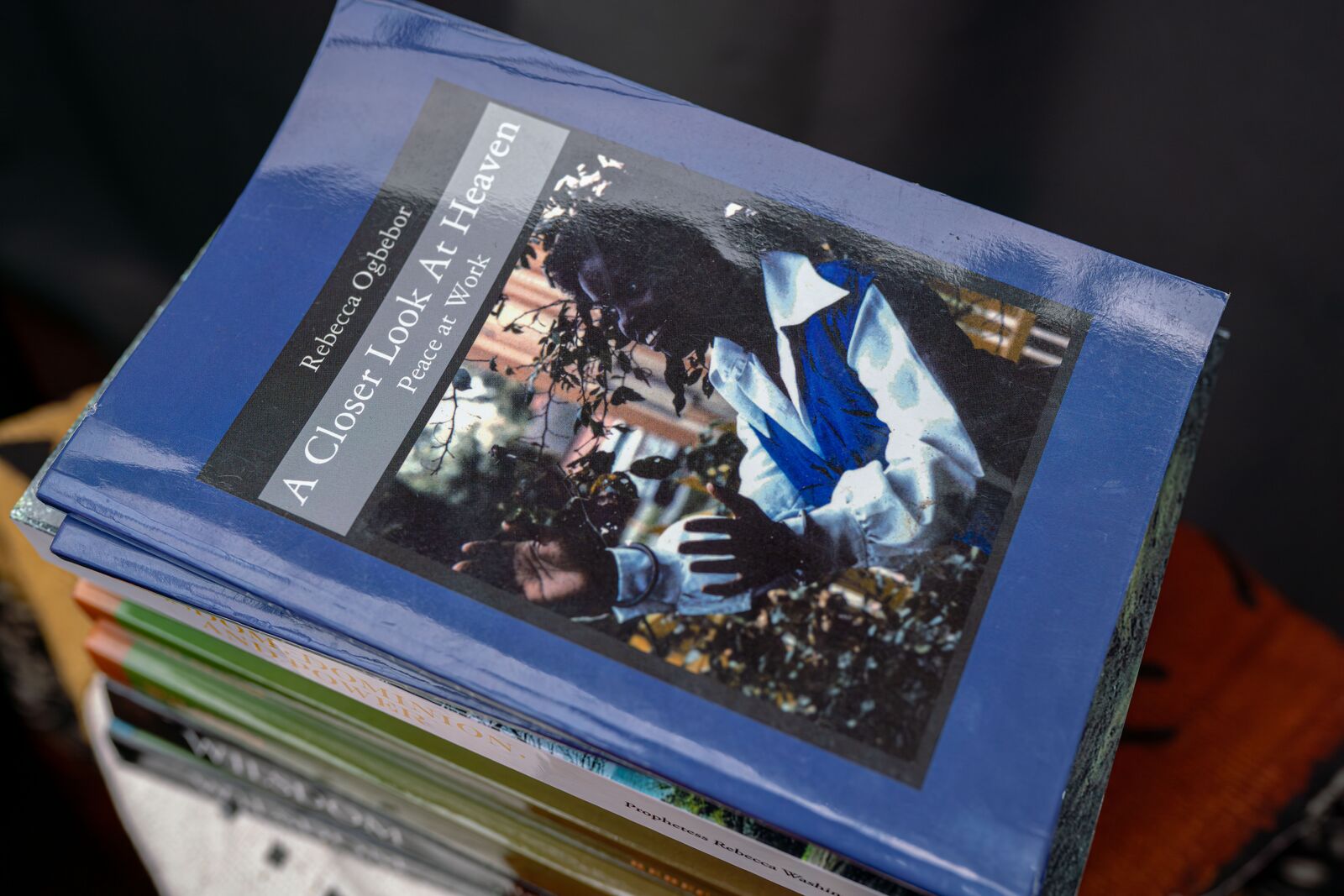

In addition to “the spirit of [her] ancestors” giving her strength, she said, Washington-Ogbebor’s faith plays a major role in her life. An ordained minister through the Living Hope Gospel Ministries International, Washington-Ogbebor is a published author of four books, all of which detail her life and spiritual journey.

Her latest book, “Wilsdom, Dominion, and Power: (A Full Circle),” is accompanied by a soundtrack that Courage Ogbebor—her youngest son and an alumnus of Oakland School for the Arts—wrote and composed himself.

Washington-Ogbebor hopes to spread her message of faith, love, and hope. When she’s not working on garments, she enjoys speaking with youth and empowering them.

“I’m always making sure that these young people are doing something different with their lives,” she said. “We don’t need more jails and incarceration and deaths.”

Note: This story has been corrected to identify Courage Ogbebor as Washington-Ogbebor’s youngest son, not grandson.