Oakland uses ranked-choice voting to elect its mayor, city council, school board, and other positions. Although the city has been using this voting system for twelve years, many people still have questions about how it works and the problems it’s trying to solve.

This post answers some of the most common questions about ranked-choice voting in Oakland and beyond and provides background on the effect it’s had on our elections.

If you think we missed something, let us know, and we’ll consider making an update.

What is ranked-choice voting?

Ranked-choice voting is probably best explained in contrast to traditional elections.

The system Oakland used until 2010—a method that’s still in use at the county and state level—is to hold a primary election, usually in June, allowing anyone who wants to run for office to throw their hat in the ring. This is how we currently elect our county sheriff, district attorney, and supervisors. The two top vote-getters in the June primary then advance to the general election in November, and voters pick the ultimate winner.

There are some criticisms of this system.

It’s expensive to hold two elections—first the June primary to whittle down the field of candidates, and then the November general election. For example, the 2006 primary election for Oakland mayor, city council, and other offices was estimated to cost city taxpayers about $800,000, according to the Oakland Tribune.

Another concern is low participation in the June primaries, a time many voters don’t think of as voting season. White and upper-income groups tend to participate in them at much higher rates than low-income people and people of color. The result is that more privileged groups get a much bigger voice in picking the top two candidates who face off in the fall.

Ranked-choice voting is seen as a solution. There’s no June primary, saving money, and turnout among all groups is boosted because voters have to fill out only one ballot for important offices like Oakland mayor, and this happens in the fall when big state and national races are also on the ballot.

But one criticism of ranked-choice voting is that it can confuse voters since it’s complicated in its own way.

OK, so how does it work?

Instead of choosing a single candidate, voters get to rank multiple candidates in order of preference.

When election officials count the ballots, if any candidate got more than 50% of all voters’ first choices, they win the election. It’s over. No more ballot counting.

But this rarely happens in races where there are three or more people running—which is common in city campaigns for mayor, council, and school board. Most of the time, no single candidate gets a majority of first-choice votes. When this happens, election officials begin the instant runoff process that’s at the core of ranked-choice voting.

First, the candidate with the lowest number of first-choice votes is eliminated, and their supporters’ second choices are distributed among the remaining candidates. If this puts any candidate over 50% of the total votes, then they win, and the runoff is over.

However, it often takes several rounds of elimination for a winner to emerge.

What’s the history of ranked-choice voting in Oakland?

In 2006, the City Council placed a measure on the ballot to change Oakland’s election system. Voters approved the measure, and the first ranked-choice election was in 2010 when voters picked a new mayor and City Council and school board members for districts 2, 4, and 6.

The 2010 election made waves—and national headlines—because it showed the power of voters’ second and third choices to swing an election in the direction of an underdog.

With big-name endorsements and lots of campaign cash, former state Senator Don Perata was widely favored to win. After ballots were counted on election night, he led the field of 10 candidates with about 34% of all first-choice votes. In second place was District 4 Councilmember Jean Quan, with 24%, and at-large Councilmember Rebecca Kaplan was in third place, with 22%.

As the tenth, ninth, eighth, seventh place candidates, and so on, were eliminated, their second-place votes started getting redistributed among the remaining candidates, with most of these going to Perata and Quan.

After eight elimination rounds, Perata gained only 8 points and reached 40% of the vote. Quan and Kaplan were trailing with 31% and 29%.

Then Kaplan was eliminated. Her voters had overwhelmingly picked Quan as their second or third choice, propelling her to victory with 51% of the vote to Perata’s 49%.

Perata conceded but then complained that ranked-choice voting wasn’t fair and said he should have won the election. The group Fair Vote, which supports ranked-choice voting, responded to Perata’s complaints, stating that they and other elections experts don’t think the outcome would have been much different had the election been held as a primary in the spring with Perata and Quan facing off in a fall general election by themselves.

Since then, there hasn’t been much, if any, controversy around ranked-choice voting in Oakland.

Cynthia Cornejo, the deputy registrar of voters, who helps develop and analyze voting policies, told The Oaklandside she thinks Alameda County residents have adapted to the ranked-choice voting and generally understand it.

“There have been no issues,” she said. “Voters are intuitive; if they don’t know, they ask.”

What’s new in this year’s election?

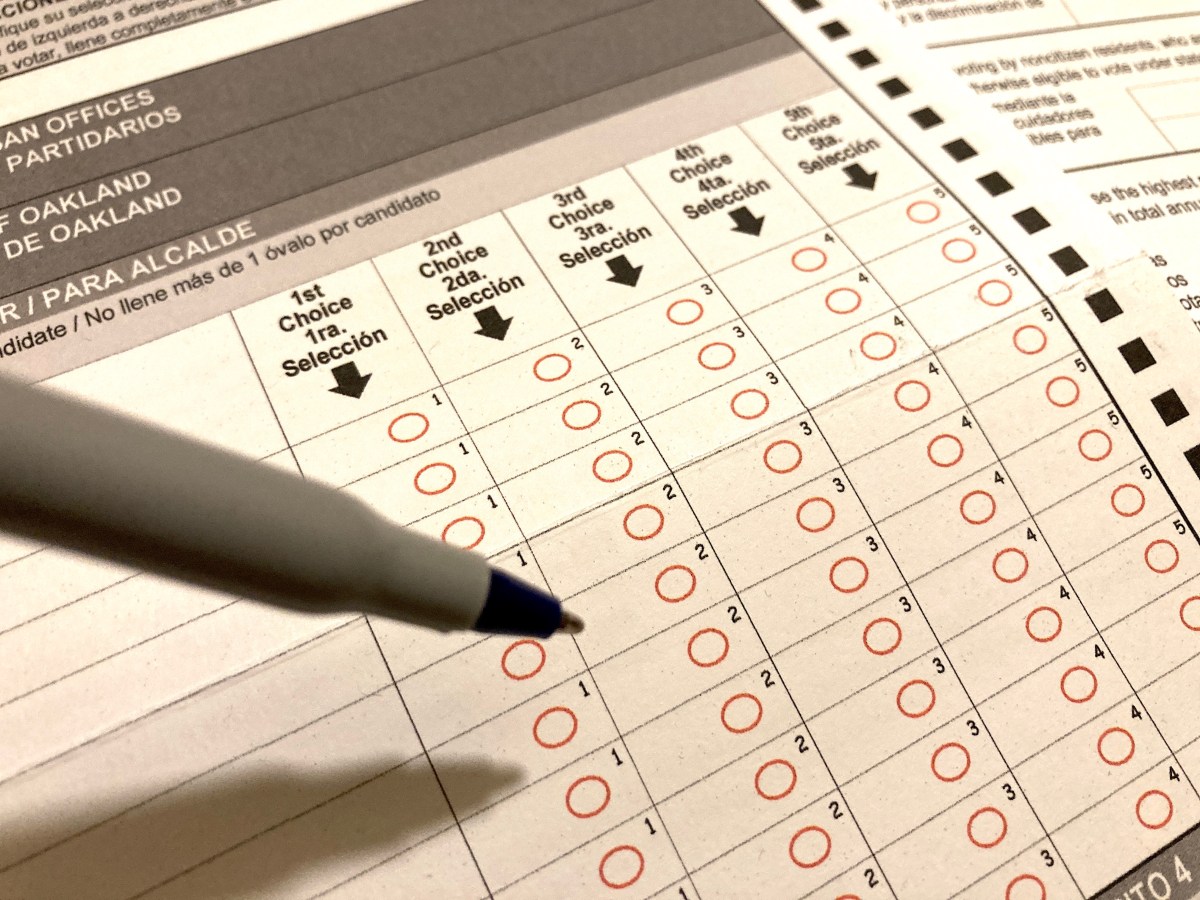

In previous years, Oakland voters could pick only their top three favorite candidates. But under an updated county election law, Oakland voters now have the option to rank up to five candidates in races for mayor, city attorney, City Council, auditor, and OUSD board. (This year, the only race with more than five candidates running is mayor.)

Deputy Registrar Cornejo told The Oaklandside the county moved from three to five candidates because it gives people more options and allows outsider candidates to have a better chance at winning.

Oakland voters have consistently ranked the maximum number of candidates on their page, taking full advantage of the voting strategies offered by the system. In 2010, 72% of Oaklanders ranked their top three candidates, and that number has stayed about the same or gone up since.

It is important to note that voters don’t have to rank five candidates. They can pick just one or rank any number up to five.

The 2022 General Election will be the second to use universal mail ballots, which means it could take longer for the registrar to count all the votes and conduct the instant runoff process. This is because Oakland voters tend to return their ballots by mail, dropbox, or in person at a voting center close to or on election day, and it takes a while for the registrar to count and tally enough of the ballots and manage the ranked-choice process to be confident in an outcome.

Be prepared to wait a while for final results in close races, much like what happened in last June’s primary election with the campaigns for sheriff and county schools superintendent, where it took a week to know the winners.

Does ranked-choice voting impact how candidates run their campaigns?

Because it’s necessary for candidates to pick up extra votes in the instant runoff process, they have a big incentive not to alienate supporters of their opponents. There’s even logic to running as a coalition with like-minded candidates to increase the possibility that someone with similar views will win the election.

In this year’s Oakland mayor’s race, some progressives are pursuing a strategy of asking voters to rank Sheng Thao, Allyssa Victory, and Greg Hodge as their only three choices, in whatever order they like. This will ensure that if Sheng Thao is eliminated in an early round of counting, the majority of her votes will go to Hodge and Victory. Or if Hodge and Victory are eliminated at some point in the count, Thao will pick up their votes, propelling her ahead of candidates whose views on issues like public safety, housing, and the budget are much more different than hers.

A group of individuals who have supported Libby Schaaf in past mayor’s races has formed a political action committee to jointly support Loren Taylor, Ignacio De La Fuente, and Treva Reid in a similar strategy.

The League of Women Voters has recommended that people vote only for candidates they genuinely like, even if it’s only two or three, because a person on the back end of the ballot might get a surprising boost through the RCV system.

Where else is ranked-choice voting used?

Ranked-choice voting has been around for more than a century. Both Ireland and Australia have used it since 1921 and 1919, respectively.

In the U.S., more than fifty cities adopted ranked-choice voting in the last decade, including Portland, Maine, and Saint Paul, Minnesota.

In the Bay Area, San Francisco, Berkeley, and San Leandro use ranked-choice voting. San Francisco was first in 2004, 10 years after a voter referendum created the San Francisco Elections Task Force to improve elections, and a grueling two-person runoff in 2002 between Gavin Newsom and Matt Gonzales led to lawsuits and reform demands.

Studies have found that giving people more options incentivizes candidates to work harder for their votes. And according to FairVote, a voting-access advocacy nonprofit, it also leads to greater diversity in elections. In New York’s 2020 election, ranked choice allowed more people from different communities to run for office, leading to historic gains in racial and gender representation—people of color won 35 out of the city’s 51 council seats, and more women were elected than in any previous election.

What experts say about ranked-choice voting

Election experts say that ranked-choice voting generally makes for a more participatory and democratic process. But it’s still a relatively new system, and there’s a lot to learn about its effects.

University of Missouri, St. Louis Political Science professor David Kimball says people’s decision to vote is largely influenced “by the costs and benefits associated with voting, as well as the probability that one’s vote will determine the outcome.” Some of these costs include learning about the candidates and figuring out how to vote.

If a person in Oakland has not voted in 15 years and has decided to participate in this election, for example, it’s possible they could be confused by ranked-choice voting and decide not to vote after all. This is because a ranked-choice ballot is slightly more complicated to fill out, with multiple columns that facilitate a voter’s preferences.

In a survey about a decade ago, University of Minnesota political science professors Lawrence Jacobs and Joanne Miller found that people who participate in ranked-choice elections have attained more education and know more about the voting process than those who don’t participate. This suggested, they said, that people not confident in the system were less likely to vote.

But the positive aspects of ranked-choice voting can counteract the negatives. Knowing their vote for a candidate counts, even as a third or fourth choice, can lead to people working harder to learn about who’s running and take time to cast a ballot.

According to a group of three researchers at the Center for State Policy and Leadership at the University of Illinois-Springfield, it also gives people a more positive attitude toward democracy.

University of Illinois researchers Manuel Gutiérrez, Alan Simmons, and John Transue found that people who vote in ranked-choice elections tend to feel better about their government, which might reduce political polarization. Survey respondents told them that even if their candidate didn’t win, they still felt like their voice was heard, and they were able to vote for a person who matched their beliefs most closely.

“If you vote in a ranked-choice election for, say, a libertarian candidate, and he doesn’t win, you are still able to vote your conscience. ‘I’m not going to waste my vote,’ they say. You can vote for who you want,” Gutiérrez told The Oaklandside.